This post will hit a bit closer to home for me as a project manager. One of the details of my job is negotiating with several stakeholders to establish project schedules and determining project end dates. But how do we provide a project end date (and milestone end dates) when practically all projects have some sort of scheduling uncertainty due to known and unknown risks? The unfortunate truth is, we can’t. It’s practically impossible to forecast an end date with 100% certainty. Even the simplest, repetitive project can’t possibly have 0% risk because obstacles can erupt outside the project’s control (systematic risks, such as weather disasters, economic disasters, et cetera).

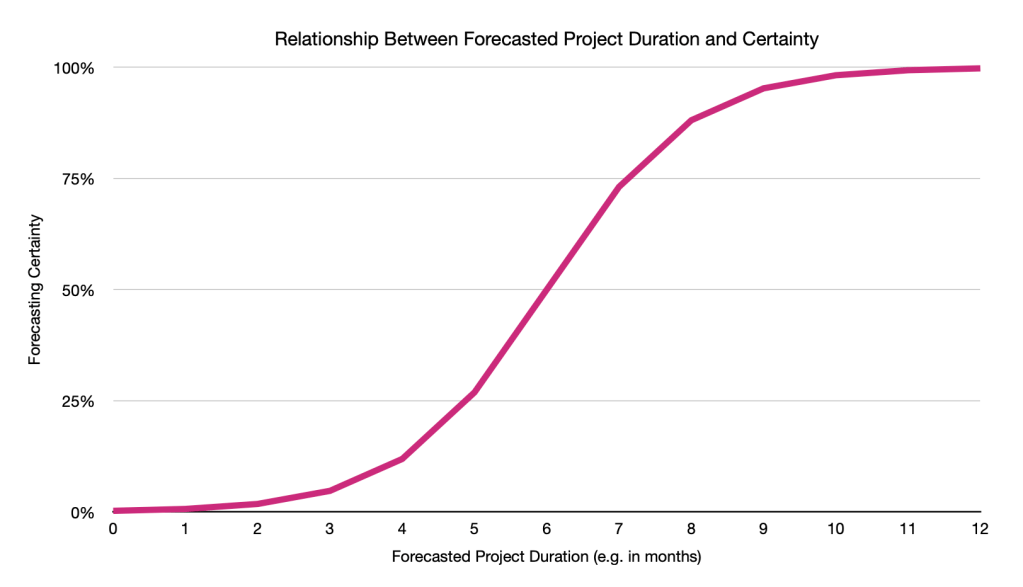

I’ve been thinking about the relationship between forecasted project duration and certainty for a bit and I’ve developed a theory about their relationship. The relationship is a sigmoid function, which looks like this:

The above curve will be different for each project due to project-specific factors, but the general shape will look similar. The first few units of time (for example, days, months, years), the likelihood of completing the project will be near 0%. After some time passes, the chances the project will complete accelerates. The speed of which it accelerates is highly dependent on the number and intensity of risks that can derail the project schedule. Eventually, certainty reaches a point of diminishing returns because no one can ever be absolutely 100% certain about how long a project will take (and the sigmoid curve will accordingly never actually hit 100%).

How can this theory be used in practice? It can be a powerful tool for negotiating project schedules. For example, in famous fashion, customers often want the project output as soon as possible (of course, at perfect quality and at the lowest cost). Unfortunately, these pressures reflect idealism rather than realism. Using the example chart above, they might try to negotiate a schedule that gets the project done in 6 months. Is that reasonable? Well, this particular project has a roughly 50% chance of being done in 6 months. It’s possible, but flip a coin and see if you’re lucky. If the project lands on the unlucky side of the coin, additional work has to be done to reevaluate the schedule with stakeholders, which can be a cost and pain in itself. I would argue for a project timeline of 9 months, which is 95% certain. Way better than 50% certain.

This theory highlights the infamous reputation for projects always being late and over budget. Project managers often want to please their customers and will fall for their demands of forecasting an earlier project end date at significantly higher rates of uncertainty. Continuing with the above example, providing a more realistic project duration, with higher certainty, would statistically fix projects’ infamous lateness reputation. If we schedule projects up to even 90% certainty, then projects will only be late 10% of the time—in other words, only 1 in 10 projects. 95% certain project durations would mean, statistically, only 1 in 20 projects would be late.

As far as further research opportunities go for this theory, I’m undecided how the curve should start. A proper sigmoid function never actually hits 0%, but the ability to complete a project is, perhaps arguably, 0% for some time in its beginning. On the other hand, maybe a project does always have the slight possibility of completing even at its kickoff. Maybe someone thinks of a workaround that negates the need for the project, or the project is canceled for some other reason? But if, for example, someone is building a pool, it’s clear that the pool doesn’t even have a 0.01% of being complete at its kickoff; it would surely be an absolute 0% chance. Maybe I’ll revisit this in the future.

Leave a comment